By Steve Cichon

By Steve Cichon

steve@buffalostories.com

@stevebuffalo

When our 1880 map of Buffalo was first printed, Millard Fillmore had died only six years earlier and was someone who would have been a familiar city father among the people of Buffalo.

When our 1880 map of Buffalo was first printed, Millard Fillmore had died only six years earlier and was someone who would have been a familiar city father among the people of Buffalo.

After moving as a teen with his father from central New York to East Aurora, Fillmore taught high school and was admitted to the bar. He was elected to the state Assembly, and after three terms, moved to Buffalo, where his burgeoning law practice could thrive. He moved to Buffalo in 1832, the year Buffalo became a city. Fillmore helped write the charter.

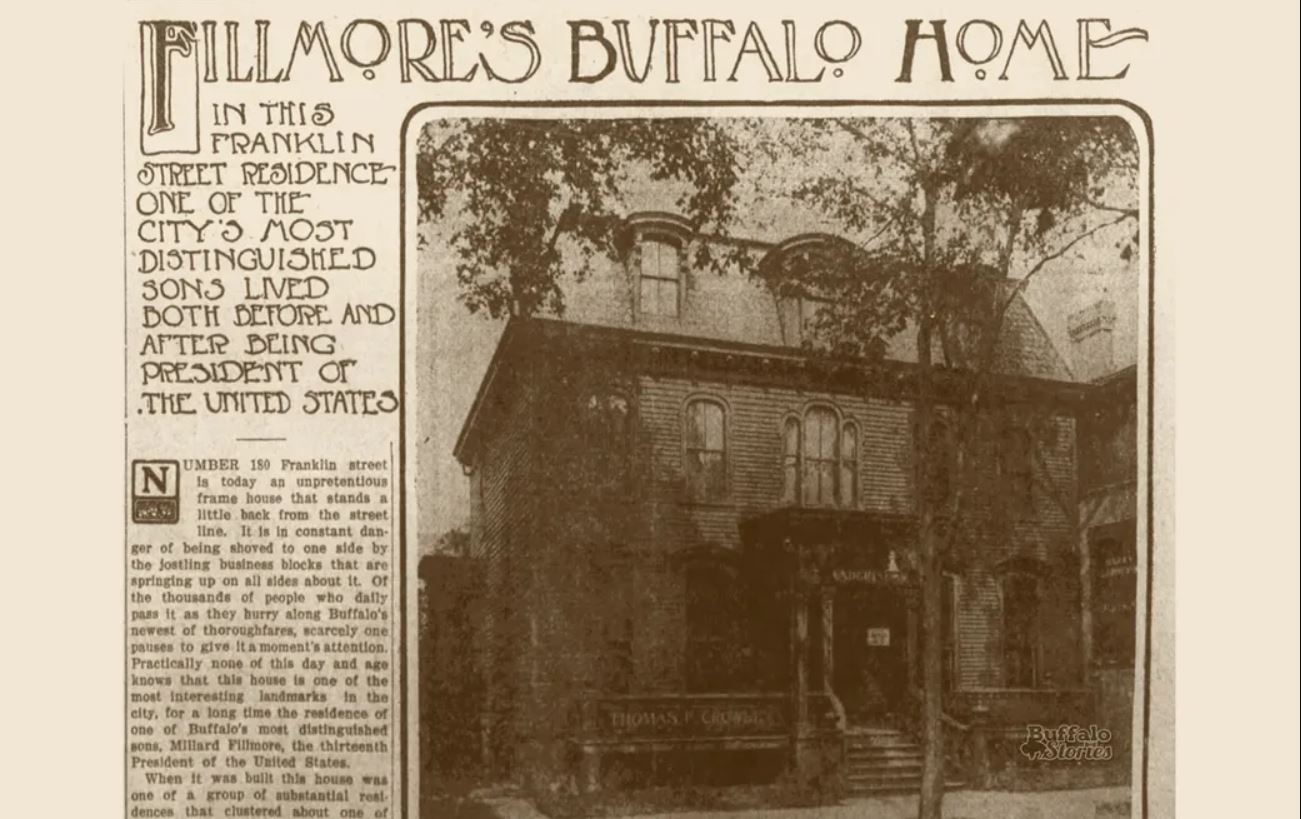

As Fillmore was elected to Congress, then to state comptroller and then, eventually, to vice president, he lived in the home pictured above on Franklin Street between Huron and Mohawk.

Even for several years after leaving the White House in 1853, the Fillmores continued to live in the same Franklin Street home.

In 1858, Fillmore moved to a grand mansion a block south on Niagara Square. The larger Fillmore residence became the Castle Inn Hotel after his death in 1874.

That building was demolished in 1921 to make way for the Statler Hotel – which was the largest hotel in the country when it was built.

During the years that Fillmore lived in Buffalo following his presidency, he continued to follow the tradition of the time and not return to business. Instead, he became intricately involved in the affairs of building many of the great institutions of the growing city.

Aside from helping write the city charter, Fillmore also was one of the founding principals of UB, the Buffalo Historical Society, the local SPCA, the homeopathic hospital that eventually bore his name and dozens more endeavors.

But now, and even in his own time, many of Fillmore’s accomplishments have been heavily overshadowed by his stance on slavery. While he was personally against slavery, he didn’t feel the federal government had any jurisdiction in eliminating it. Moreover, as president, he signed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which greatly hampered the ability for slaves to escape to freedom.

Fillmore’s Niagara Square home made national news when Buffalonians showed their displeasure with the ex-president.

At the start of the Civil War, Fillmore solidly backed President Abraham Lincoln, even commanding a section of volunteers too old to fight at the front lines, but trained to protect Buffalo in the case of an attack.

Fillmore, however, lost confidence in Lincoln and eventually backed Democrat George McClellan for president, with the understanding that McClellan would have worked to reunite the country, even if it meant slavery would survive.

When Lincoln was assassinated, homes and businesses in Buffalo and around the nation were covered in black bunting and American flags. Fillmore’s house on Niagara Square was a notable exception. Pro-Republican newspapers around the country reported that in reaction to Fillmore’s lack of decorum, a mob flung ink (or in some reports mud) on his home. Many of these reports were gleeful, a few just crude. But the partisan reports were “fake news” 150 years before the term was coined.