By Steve Cichon

By Steve Cichon

steve@buffalostories.com

@stevebuffalo

County Donegal, along Ireland’s northern coast, is the ancestral home of my branch of the Coyle Family.

Insulated from the rest of the country by mountains and bogs, the specific Tullaghobegley Parish area near Gweedore where the Coyles come from was the poorest and least fertile districts in all of Ireland.

The Coyles in Ireland

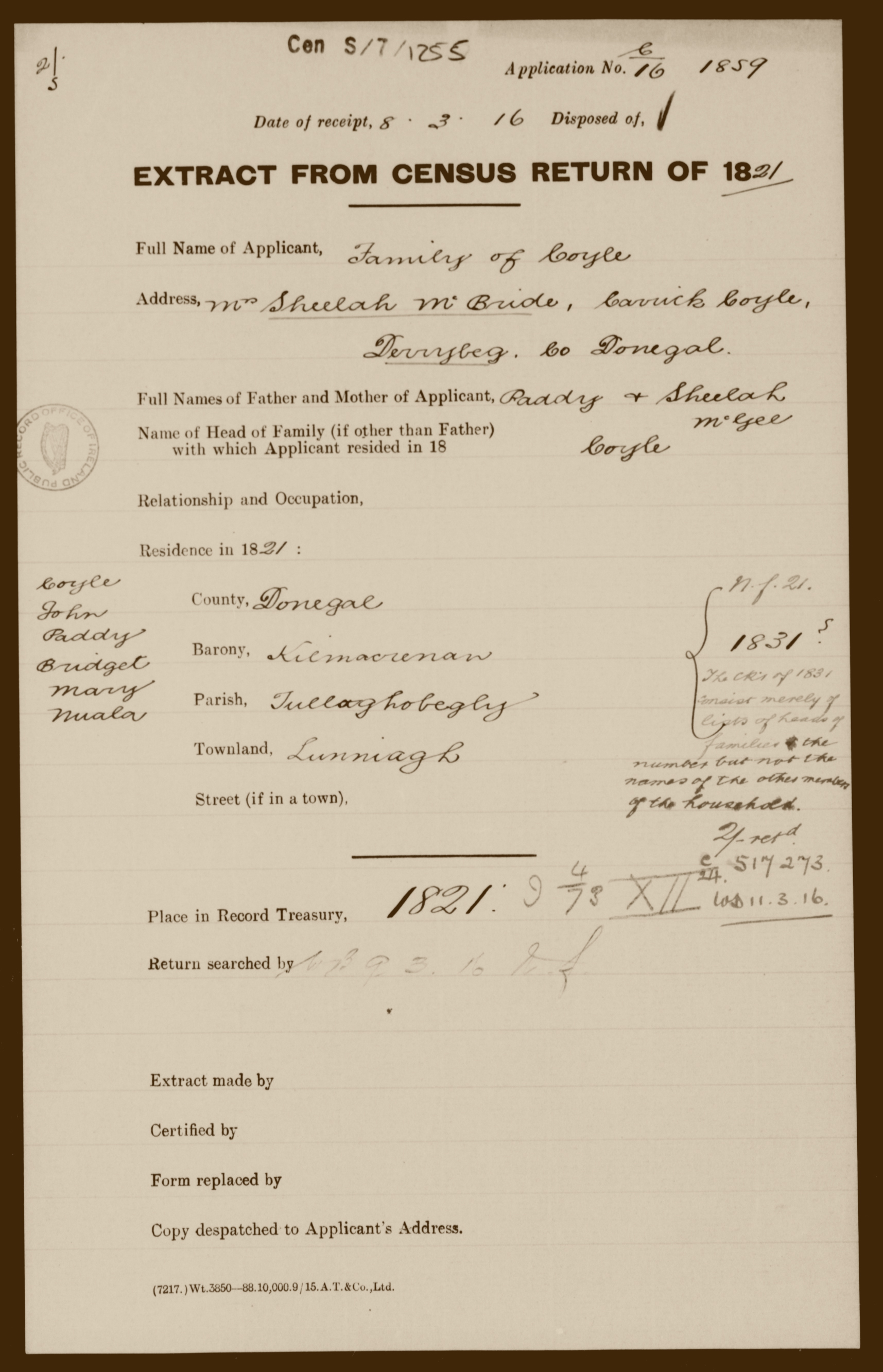

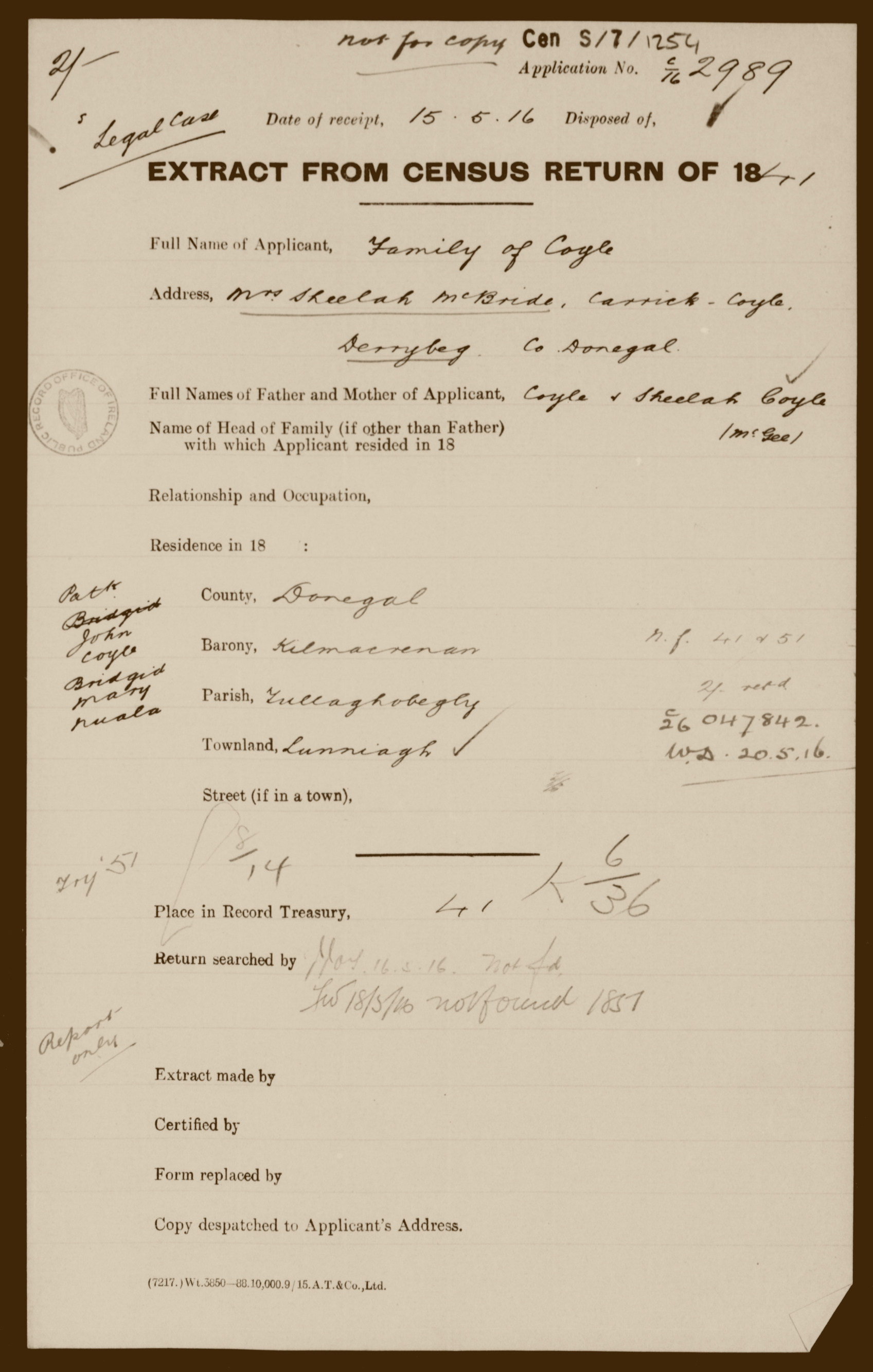

The Paddy Coyle who is the head of household on these 1821 and 1841 census abstracts is the father of the John and Patrick who are listed in the 1857 Griffiths Evaluation. He is also the grandfather of the three Coyles who left County Donegal for Pennsylvania coal country in the mid-1800s. Paddy Coyle and Sheelah McGee-Coyle are my fifth-great grandparents.

Patrick and John Coyle, sons of Paddy Coyle and Sheelah McGee-Coyle, and their cousins, Cormack and John McGee, shared plot 4A in the 1857 Griffiths Valuation in Lunniaghbeg, Parish of Tullaghobegly, in 1857.

This Patrick Coyle was married to Cecilia McGee-Coyle. They are my fourth-great grandparents, and the parents of John Coyle, who later left for America.

This map illustrates the Coyle and McGee plots as recorded in Griffith’s Evaluation, 1857.

Three children of the Patrick Coyle from the Griffith Evaluation left Lunniaghbeg, Tullaghobegley Parish, County Donegal through the mid-1800s, coming to America and winding up in Pennsylvania’s coal mines.

Coyles in America

Each of those three Coyles who emigrated to the US may have eventually married spouses with ties to the families left behind in Lunniagh.

Frances “Fanny” Coyle (c.1847-1916) did for sure. She married John Gallagher at St Mary’s in Tullaghobegly near Gweedore in 1870 before they moved to Jermyn, PA. They had two children, Charles and Margaret. John was crushed to death working as a laborer in the Delaware & Hudson mine. She died in Pennsylvania in 1916.

Bridget Coyle (c.1842-1907) was the second wife of John McGee. They married in Pennsylvania in 1866. There were at least six McGee children. It’s not clear whether McGee was a cousin from Lunniaghbeg, but he did come to Audenreid, PA in the 1850s from Ireland. He died in 1903 from “miner’s asthma.” Bridget died in the mine town of McAdoo, PA in 1907.

John Coyle (c.1849-1908) married Mary Dugan in Pennsylvania in 1865. It’s possible—but it’s unclear whether Mary’s mother, Rose Gallagher-Dugan, was related to the Gallaghers of Lunniaghbeg. John and Mary Coyle had eight children, including my great-great grandfather, Patrick Coyle, who was born in 1872. He moved his family from Scranton, PA to Buffalo, NY following the death of his mother in 1916.

Gweedore

Gweedore was one of the most infamous spots in Ireland in the mid-19th century, and was the next town over from the Coyle home of Lunniagh.

Most of the population there were ethnic Irish Catholics who were displaced from more fertile land that was resettled by British Protestants. The soil around Gweedore is rocky, unforgiving, and very difficult to make yield anything edible for people or livestock—except for the places where it is too soft and boggy.

“Although there are signs of human habitation in the Gweedore area, including the remains of a medieval church at Magheragallan, indicating that the area has long been inhabited, the population of this ‘remote and inhospitable area’ probably only began expanding ‘during the seventeenth century as a result of population displacements associated with the Ulster Plantation.’” -History of Gweedore, Tim O’Sullivan, 2002. (This history is posted on a great site about the history of this area, http://donegalgenealogy.com/chapter_one.htm)

A mountainous border surrounding the area and the elsewhere marshy earth made for few roads leading in or out. The Irish language was the only language spoken by many, and the land was occupied according to the medieval Rundale system as late as the mid-1800s. Clachan houses of individual families surrounded the larger rundale plots which they farmed together.

When tax collectors came to Gweedore in the 1830s, they were beaten, their arms confiscated, and they were turned back.

Not only did the people of Gweedore, Lunniagh and surrounding areas not want to pay taxes to the British crown or tithe to the Church of England—they didn’t have much to give.

Patrick McKye, teacher in the National School, wrote a letter to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1837 describing the horrific conditions in the parish that the Coyles called home.

“That the parishioners of this parish of Tullaghobegly… are in the most, needy, hungry, and naked condition of any people that ever came within the precincts of my knowledge, although I have travelled a part of nine counties in Ireland, also a part of England and Scotland, together with a part of British America. I have likewise perambulated 2,253 miles through some of the United States, and never witnessed the tenth part of such hunger, hardships, and nakedness.”

“None of their either married or unmarried women can afford more than one shirt, and the fewest number cannot afford any, and more than half of both men and women cannot afford shoes to their feet; nor can many of them afford a second bed, but whole families of sons and daughters of mature age indiscriminately lying together with their parents, and all in the bare buff.

“Their beds are straw, green and dried rushes, or mountain bent; their bed clothes are either coarse sheets or no sheets, and ragged, filthy blankets.

“And more than all that I have mentioned, there is a general prospect of starvation at the present prevailing among them, and that originating from various causes; but the principal cause is a rot or failure of seed in the last year’s crop, together with a scarcity of winter forage, in consequence of a long continuation of storms since October last in this part of the country.

“So that they, the people, were under the necessity of cutting down their potatoes, and give them to the cattle to keep them alive. All these circumstances connected together have brought hunger to reign among them, in that degree that the generality of the peasantry are on the small allowance of one meal a day, and many families cannot afford more than one meal in two days, and sometimes, one meal in three days. Their children crying and fainting with hunger, and their parents weeping, being full of grief, hunger, debility, and dejection, with glooming aspect looking at their children likely to expire in the pains of starvation.”

Lord George Hill was the British landowner who worked to improve the lives of the people in his care—but at the same time worked to undermine their identity and way of life. He wrote a pamphlet called “Facts from Gweedore,” which made both of those goals easily apparent. He called the people of the area “more deplorable than can well be conceived; famine was periodical, and fever its attendant; wretchedness pervaded the district.”

In the wake of a particularly striking famine in 1858, parish priests in the area wrote an appeal to Queen Victoria and to the people of the world begging for help.

“In the wilds of Donegal, down in the bogs and glens of Gweedore and Cloughaneely, thousands and thousands of human beings, made after the image and likeness of God, are perishing, or next to perishing, amid squalidness and misery, for want of food and clothing, far away from aid and pity. On behalf of these famishing victims of oppression and persecution, we appeal for substantial assistance to enable us to relieve their wretchedness, and rescue them from death and starvation.

“There are at the moment 800 families subsisting on seaweed, crabs, cockles, or any other edible matter they can pick up along the seashore or scrape off the rocks. There are about 600 adults of both sexes, who through sheer poverty are now going barefoot, amid the inclemency of the season, on this bleak northern coast. There are about 700 families that have neither bed nor bedclothes… Thousands of the male population have only one cotton shirt; while thousands have not even one. There are about 600 families who have neither cow, sheep, nor goat and who…hardly know the taste of milk or butter.

“This fine old Celtic race is about being crushed to make room for Scotch and English sheep.”

It was around this time that a teenaged John Coyle left for America to make a new life in coal mines.

The story continues…..