By Steve Cichon

By Steve Cichon

steve@buffalostories.com

@stevebuffalo

Buffalo men of a certain age react one of two ways at any mention of the Palace Burlesk: Whimsical and easy smiles or tense and dyspeptic discomfort. The reaction is usually based on whether the man’s ribs happen to be close enough to catch an elbow from a wife who knows all too well what those smiles are about.

The last show at the Palace Burlesk’s original location in 1967.

Burlesque sounds bawdy enough when it ends with “–que,” but when it ends with a “–k,” as it did for most of the 50 years Dewey Michaels ran downtown Buffalo’s most famous and infamous live girlie show, you knew what you were going to get.

A far cry from the “Canadian Ballet” style of “gentlemen’s entertainment” in later eras, the Palace Burlesk women bared a lot — but certainly not all. There was dancing, Vaudeville comedy, the occasional animal act, short films and always live music.

Rest assured that when your father or grandfather went to the Palace, it wasn’t for the Borscht Belt Jewish comedians who had been at the top of their game 30 years earlier — but the mix of entertainment made it likely that there might also be more than just the odd woman there for the show.

The Palace and Shelton Square, late 1940s. (Buffalo News archives)

The Palace Burlesk was the crown jewel of Shelton Square, known for decades as Buffalo’s Time Square. Both the Palace and Shelton Square were wiped off the map in the late ’60s, when the tightly packed, century-old buildings were wiped out for the Main Place Tower, the M&T Building and the green space along the east side of Main at Church, where the Palace once stood.

With the M&T headquarters already built in the background, the block of buildings where the Palace stood was being torn down to make way for green space in 1967. (Buffalo News archives)

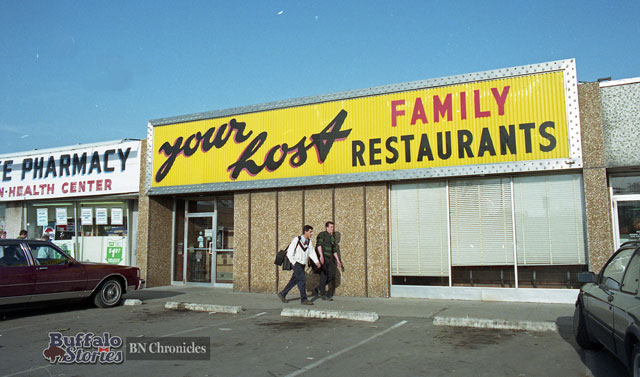

They tried to build a new Palace Burlesque at the corner of Main and Tupper, but it never caught on. Within a decade, the place was the home of Studio Arena Theatre—now known at 710 Main Theatre.

Main and Tupper, 1967 (Buffalo News archives)

In 1993, George Kunz wrote about the Palace for The News, and he does a wonderful job of describing the spirit of the place — and offering a whole host of reasons that men of a certain age might tell their wives and daughters and granddaughters why they visited the Palace.

The End of Royalty

By George Kunz

August 1, 1993

Rarely can one fix an exact date for the end of an era, but in the case of vaudeville-burlesque in Buffalo, there is an absolute date for an absolute end: April 6, 1967. On that spring evening, people gathered at the Palace Theater to see the curtain rise and fall for the final time.

It was a gala performance: all 720 seats had been sold long in advance, with big blocks of tickets bought by the Saturn and Buffalo clubs. A tall doorman in blue uniform with gold braid and buttons presided at curbside, helping guests alight onto a red carpet which stretched on into the Palace.

Long, shiny cars started arriving before 8; men in black tie, women wearing floor-length gowns. From outside the area, visitors traveled by chartered bus. Almost a thousand people squeezed into the high, narrow building.

Although the Palace had been known as a burlesque house, its programs were largely vaudeville. This entertainment, American cousin of the British music hall, once thrived in a dozen local theaters, but movies gradually stifled live performances.

One by one, showplaces shut down or converted to films until only the Palace remained as a source of employment to a generation of performers who had trained on the vaudeville stage. With a blend of burlesque and vaudeville acts, the Palace held a unique place in the heart of downtown Buffalo. Audiences were large and spirited.

Such was the theater’s fame that for years the Palace was used as a focus for any downtown geographical instructions. “You know where the Palace is … well, you turn right there.” Everybody remembered the lively marquee with the dancing girl figures kicking endlessly to the rhythm of blinking lights.

Located across Main Street from Shelton Square, the Palace exuded life. Pedestrians passing during showtime heard raucous, robust sounds of extravagant fun. The orchestra blared, drums rumbled and laughter, a rollicking outrageous laughter, tumbled out the doors onto Main Street.

When I was a kid, my mother and I would sometimes pass on the way to catch a South Park trolley. Mother had just made the weekly novena at St. Joseph’s Cathedral, and she would hustle me by the Palace, hoping that I would not notice the hilarity.

Old by American standards, the Palace was built shortly after the Civil War. The three-story edifice was faced with white marble and sparkled with lights, with joie de vivre. Inverted V signs pictured the week’s headliners: girls posing naughtily with their fans, veils, feathers. Smaller posters advertised an accompanying movie, but this was incidental. The Palace specialized in live entertainment.

An old Buffalo joke had it that to receive a high school diploma, young men, at least once, had to skip the day’s classes and attend the Palace Burlesque. Only then could an education be considered complete.

The Palace was ready to satisfy such graduation requirements: On weekdays, the first show began at noon; four other performances followed. A final midnight special was added on Saturday.

To describe a Palace midnight show is to resurrect a bygone era. Waiting for a performance, hucksters circulated among the audience, peddling popcorn, ice cream suckers, candy, programs. The atmosphere resembled that surrounding a hockey game.

Generally, all seats were filled, and with a lively drum roll, the orchestra started its overture, the curtain rose and the chorus danced out to enthusiastic applause. In front were always the better dancers, the more lissome girls; behind them, the veterans whose prime had been kicked over the footlights of many stages.

After this boisterous introduction, a master of ceremonies took command, introducing individual acts: singers, jugglers, magicians. The featured solo dancers were, of course, alluring and deeply appreciated by students. They always performed under soft blue lights.

The best part of any Palace show was the comics. Rag-tag survivors of a dying vaudeville, the baggy-panted comedians worked their old routines. Wonderful, funny, talented performers they were — the last of a breed that knew it was vanishing.

Sometimes they wove the lead dancers into their skits, and the contrast between beauty and the fools was uproarious. Such acts were usually without vulgarity, reminiscent of the French farces of Georg Feydeau. Compared with modern television, they were touchingly innocent.

A staple of any Palace burlesque show was the closing promenade. The music of Irving Berlin’s classic “A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody” was unvarying background. While the emcee droned the lyrics, the girls, quite tired by now, crossed the stage one final time.

Great burlesque queens played the Palace: Evelyn Nesbit Thau and Rose la Rose. But the comics are the stars who deserve to be immortalized: Abbott and Costello, Phil Silvers, W.C. Fields, Mickey Rooney, Red Buttons, Jerry Lewis, Sammy Davis Jr. and a host of gentle, forgotten vaudevillians.

For that last, era-closing performance in April 1967, some famous personalities came out of retirement: Hal Haig, one of the original Keystone Kops; Bert Karr with a legendary vaudeville ice cream routine; Lenny Paige, a longtime local stage celebrity, was master of ceremonies.

Awards were presented to the Palace’s respected owner-showman, Dewey Michaels, who also operated the Mercury, an art theater out Main Street. Michaels had bowed to the rights of eminent domain and sold his theater to New York State so that the Church Street Arterial could be built.

Michaels invested that payment in a new burlesque theater at Main and Tupper streets. Unhappily, the medium did not survive the transplant; the patrons were indifferent and few.

In September 1977, this new, ill-fated theater was sold; the operation went highbrow and became the Studio Arena Theatre. As such, it still offers live entertainment in Buffalo’s Theater District, although not quite in the old Palace tradition.

By Steve Cichon

By Steve Cichon